"Rock Island Line" by Lonnie Donegan

A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

Welcome to episode twenty of A History of Rock Music in Five Hundred Songs. Today we're looking at "Rock Island Line" by Lonnie Donegan. Click the full post to read liner notes, links to more information, and a transcript of the episode.

----more----Erratum

I say in the episode that rationing in the UK ended the day that Elvis recorded "That's All Right Mama". In actual fact, rationing ended on July 4, 1954, while Elvis recorded his track on July 5.

Resources

As always, I've created a Mixcloud streaming playlist with full versions of all the songs in the episode.

The resource I've used more than any in this entry is Roots, Radicals, and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World by Billy Bragg. I thought when I bought it that given that Bragg is a musician, it would probably not be a particularly good book, and I only picked it up to see if there was anything in it that I should address, given it came out last year and sold quite well, but I was absolutely blown away by how good it actually is, and I can't imagine anyone who listens to this podcast not enjoying it.

This five-CD box set of Lonnie Donegan recordings contains over a hundred tracks for ten pounds, and is quite astonishing value.

And this collection of Lead Belly recordings is about as good an overview as you're likely to get of his work.

Patreon

This podcast is brought to you by the generosity of my backers on Patreon. Why not join them?

And why not back the Kickstarter for a book based on the first twenty episodes?

Transcript

In this series, so far we've only looked at musicians in the US -- other than a brief mention of the Crew-Cuts, who were from Canada. And this makes sense when it comes to rock and roll history, because up until the 1960s rock and roll was primarily a North American genre, and anyone outside the US was an imitator, and would have little or no influence on the people who were making the more important music.

But this is the point in which Britain really starts to enter our story. And to explain how Britain's rock and roll culture developed, I first have to tell you about the trad jazz boom.

In the fifties, jazz was taking some very strange turns. There's a cycle that all popular genres in any art-forms seem to go through – they start off as super-simplistic, discarding all the frippery of whatever previous genre was currently disappearing up itself, and prizing simplicity, self-expression, and the idea that anyone can create art. They then get a second generation who want to do more sophisticated, interesting, things. And then you get a couple of things happening at once -- you get a group of people who move even further on from the "sophisticated" work, and who create art that's even more intellectually complex and which only appeals to people who have a lot of time to study the work intensely (this is not necessarily a bad thing, but it is a thing) and another group whose reaction is to say "let's go back to the simple original style".

We'll see this playing out in rock music over the course of the seventies, in particular, but in the fifties it was happening in jazz. As artists like John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, Thelonius Monk and Charles Mingus were busy pushing the form to its harmonic limits, going for ever-more-complex music, there was a countermovement to create simpler, more blues-based music.

In the US, this mostly took the form of rhythm and blues, but there was also a whole movement of youngish men who went looking for the obscure heroes of previous generations of jazz and blues music, and brought them out of obscurity. That movement didn't get much traction in the jazz scene in America -- though it did play into the burgeoning folk scene, which we'll talk about later. But it made a huge difference in the UK.

In the UK, there were a lot of musicians -- mostly rich, young, white men, though they came from all social classes and backgrounds, and mostly based in London -- who idolised the music made in New Orleans in the 1920s. These people -- people like Humphrey Lyttleton, Chris Barber, George Melly, Ken Colyer, and Acker Bilk -- thought not only that bebop and modern jazz were too intellectual, but many of them thought that even the Kansas City jazz of the 1930s which had led to swing -- the music of people like Count Basie or Jesse Stone -- was too far from the true great music, which was the 1920s hot Dixieland jazz of people like King Oliver, Sidney Bechet, and Louis Armstrong. Any jazz since then was suspect, and they set out to recreate that 1920s music as accurately as they could. They were playing traditional jazz – or trad, as it was known.

These rather earnest young men were very much the same kind of people as those who would, ten years later, form bands like the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds, and the Animals, and they saw themselves as scholars as much as those later musicians did. They were looking at the history, and trying to figure out how to recapture the work of other people. They were working for cultural preservation, not to create new music themselves as such -- although many of them became important musicians in their own right.

Skiffle started out as a way for trad musicians who played brass instruments to save their lips. When the band that at various times was led by Ken Colyer or Chris Barber used to play their sets, they'd take a break in the middle so their lips wouldn't wear out, and originally this break would be taken up with Colyer's brother Bill playing his old seventy-eight records and explaining the history of the music to the audience -- that was the kind of audience that this kind of music had, the kind that wanted a lecture about the history of the songs. The kind of people who would, in fact, be listening to this podcast if podcasts had been around in the late forties and early fifties.

But eventually, the band figured out that you could do something similar while still playing live music. If the horn players either switched to string instruments for a bit, played percussion on things like washboards, or just sat out, they could take a break from their main set of playing Dixieland music and instead play old folk and blues songs. They could explain the stories behind those songs in the same way that Bill Colyer had explained the stories behind his old jazz records, but they could incorporate it into the performance much more naturally.

And so in the middle of the Dixieland jazz, you'd get a breakout set, featuring a lineup that varied from week to week but would usually be Chris Barber on double bass instead of his usual trombone, Colyer and Tony Donegan on guitar, Alexis Korner on mandolin, and Bill Colyer on washboard percussion.

And when, for an early radio broadcast, Bill Colyer was asked what kind of music this small group were playing, he called it "skiffle". And so Ken Colyer's Skiffle Group was born.

In its original meaning "skiffle" was one of many slang terms that had been used in the 1920s in the US for a rent party. It was never in hugely wide use, but it was referenced in, for example, the song "Chicago Skiffle" by Jimmy O'Bryant's Famous Original Washboard Band:

[excerpt: "Chicago Skiffle"]

We haven't talked about rent parties before, but they were a common thing in the early part of the twentieth century, especially in black communities, and especially in Harlem in New York. If the rent was due and you didn't have enough money to pay for it, you'd clear some space in your flat, get in some food and alcohol, find someone you knew who could play the piano, or even a small band, and let everyone know there was a party on. They'd pay at the door, and hopefully you'd get enough money to cover the cost of your food, some money for the piano player, and the rent for the next month.

Many musicians could make a decent living playing a different rent party every day, and musicians like Fats Waller and James P. Johnson spent much of their early careers playing rent parties.

If a band, rather than a single piano player, played at a rent party, it would not be a big professional band, but it would be more likely to be a jug band or a coffee pot band -- people using improvised household equipment for percussion along with string instruments like guitars and banjos, harmonicas, and similar cheap and portable instruments.

This kind of music would have gone unremembered, were it not for Dan Burley. Dan Burley was a pioneering black journalist who worked as an editor for Ebony and Jet magazines, and also edited most of Elijah Mohammed's writings, as well as writing a bestselling dictionary of Jive slang. He was also, though, a musician -- he'd been a classmate of Lionel Hampton, in fact, and co-wrote several songs with him -- and in the late 1940s he put together a band which also included Brownie and Sticks McGhee (although Sticks was then performing under the name of "Globe Trotter McGhee"). They called themselves Dan Burley and His Skiffle Boys, and it was them that Bill Colyer was remembering when he gave the style its name.

[excerpt: Dan Burley and His Skiffle Boys: "South Side Shake"].

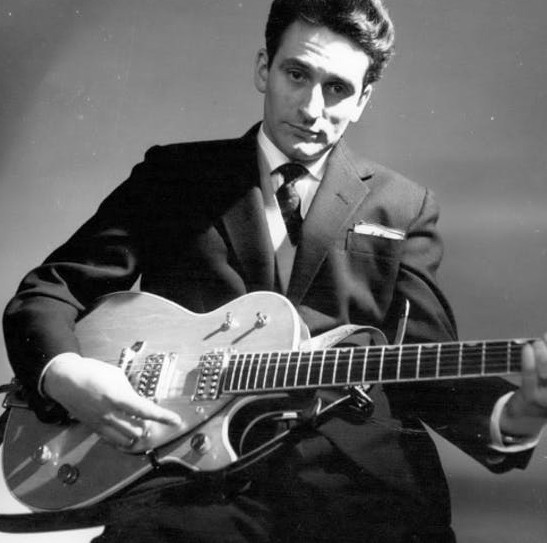

The trad jazz scene in Britain, like the overlapping traditional folk scene, had a great number of left-wing activists, and so at least some of the bands were organised on left-wing, co-operative, lines. That was certainly the case for Ken Colyer's band, but then Colyer wanted to sack the bass player and the drummer, because he didn't think they could play well, and the guitarist, now calling himself Lonnie Donegan after his favourite blues singer, because he hated him as a person. As Chris Barber later said, "Anyone who’s ever dealt with Lonnie hates his guts, but that’s no reason to fire him."

The band weren't too keen on this "firing half of what was meant to be a workers' co-operative" idea, took a vote, and kicked Colyer and his brother out instead. Colyer then made several statements about how he'd been going to leave them anyway, because they kept doing things like wanting to play ragtime or Duke Ellington songs or other things that weren't completely pure New Orleans jazz.

The result was two rival bands, one headed by Colyer, and one headed by Chris Barber, which became known unsurprisingly as the Chris Barber band.

Barber is one of the most important figures in British jazz, although he entered the world of music almost accidentally. He was in the audience watching a band play when the trombonist leaned over in the middle of the show and asked him if he wanted to buy a trombone. Barber asked how much it was, and the trombonist said "five pounds ten". As Barber happened to have exactly five pounds and ten shillings in his pocket at the time, and he couldn't see any good reason *not* to own a trombone, he ended up with it, and then he had to learn how to play it. But he'd learned well enough that by this point he was the obvious choice to lead the band.

Both bands were still wanted by the record label, and so at short order the Chris Barber band had to go into the studio to record an album that would compete with the second album by Colyer. But they didn't have enough material to make an album, or at least not enough material that wasn't being done by every other trad band in London.

So then the idea struck them to record some of the skiffle music they'd been playing in between sets, as a bit of album filler.

They weren't the first band to do this -- in fact Colyer's own band had done the same some months previously. Colyer's new band featured clarinetist Acker Bilk, who would later become the very first British person ever to have a number one record in the US, and it also featured Alexis Korner in its skiffle group. That skiffle group recorded several songs on the first album by Colyer's new lineup, including this Lead Belly song:

[excerpt: Ken Colyer, "Midnight Special"]

That's Ken Colyer, Bill Colyer, Alexis Korner, and Mickey Ashman. And that gives an idea of the polite form of skiffle that Colyer played.

But what the members of the Barber band came up with, more or less accidentally, was something that was a lot closer to the rock and roll that was just starting to be a force in the US than it was to anything else that was being recorded in the UK. In fact there's a very strong argument to be made that rock music -- the music from the sixties onwards, made by guitar bands -- as opposed to rock and roll -- a music created in the 1950s, originally mostly by black people, and often featuring piano and saxophone -- had its origins in these tracks as much as it did in anything created in the USA.

The important thing about this -- something that is very easy to miss with hindsight, but is absolutely crucial -- is that these skiffle groups were the first bands in Britain where the guitar was front and centre. Normally, the guitar would be an instrument at the back, in the rhythm section -- Britain didn't have the same tradition of country and blues singers as the US did, and it was still more or less unknown to have a singer accompanying themselves on a guitar, as opposed to the piano.

That changed with skiffle. And in particular, a record that changed the world almost as much as "Rock Around the Clock" had was this band's version of "Rock Island Line", featuring Lonnie Donegan on vocals.

"Rock Island Line" is a song that's usually credited to Huddie Ledbetter, who is better known as Lead Belly -- but, as with many things, the story is a little more complicated than that.

Ledbetter was one of the pioneers of what we now think of as folk music. He had spent multiple terms in prison -- for carrying a pistol, for murder, for attempted murder, and for assault -- and the legend has it that at least twice he managed to get himself pardoned by singing for the State Governor. The legend here is slightly inaccurate -- but not as inaccurate as it may sound.

Ledbetter was primarily a blues musician, but he was taken under the wing of John and Alan Lomax, two left-wing collectors of folk songs, who brought him to an audience primarily made up of white urban leftists -- a very different audience from that of most black performers of the time. As well as being a performer, Ledbetter would assist the Lomaxes in their work recording folk songs, by going into prisons and talking to the prisoners there, explaining what it was the Lomaxes were doing -- a black man who had spent much of his life in prison was far more likely to be able to explain things in a way that prisoners understood than two white academics were going to be able to.

Ledbetter was, undoubtedly, a songwriter of real talent, and he came up with songs like "The Bourgeois Blues":

[Excerpt: Lead Belly, "The Bourgeois Blues"]

But "Rock Island Line" itself isn't an original song. It dates back to 1930, only a few years before Lead Belly's recording, and it was written by Clarence Wilson, an engine-wiper for the Rock Island railway company. Wilson was also part of the Rock Island Colored Quartet, one of several vocal groups who were supported by the railway as a PR move to boost its brand.

In that iteration of the song, it was essentially an advertising jingle. But within four years it had been taken up by singers in prisons, and had transmuted into the kind of train song that talks about the train to heaven and redemption from sin:

[excerpt Kelly Pace: "Rock Island Line"]

In this iteration, it's closer to another song popularised by Lead Belly, "Midnight Special", or to Rosetta Tharpe's "This Train", than it is to an advertisement for a particularly good train line.

Lead Belly took the song for his own, and added verses. He also added spoken introductions, which varied every time, but eventually coalesced into something like this:

[excerpt Lead Belly "Rock Island Line"]

And it's that song, an advertising jingle that had become a gospel song that had become a song about a trickster figure of a train driver, that Lonnie Donegan performed, with members of Chris Barber's Jazz Band.

The song had become popular among trad jazzers, and one version of "Rock Island Line" that Donegan would definitely have heard is George Melly's version from 1951. Unlike Donegan's version, this was never a hit, and Melly later admitted that this lack of success was one of the reasons he wasn't a particular fan of Donegan -- but Donegan definitely attended a concert where Melly performed the song, several years before recording his own version.

Melly's version was so unsuccessful, in fact, that it seems never to have been reissued in any format that will play on modern equipment -- it's not only never been released as a download or on CD, it's never even been released on *vinyl* to the best of my knowledge! -- and it's never been digitised by any of the many resources I consult for archival 78s, so for the first time I'm unable to play an excerpt of a track I'm talking about. The only digital copy of it I've ever been able to find out about was when an Internet radio show devoted to old 78s played it on one episode nearly six years ago, but the MP3 of that episode is no longer in the station's archives, and the DJ hasn't responded to my emails. Sorry about that.

So I've no idea to what extent George Melly's version was responsible for Donegan choosing that song to record, but it's safe to say that Melly's version didn't have whatever magic Donegan's had that made him into arguably the most influential British musician of his generation.

Donegan's version starts similarly to Lead Belly's, but he tells the story differently:

[excerpt: Lonnie Donegan, "Rock Island Line"]

In his version, the line runs down to New Orleans, which is not where the real-life Rock Island Line runs -- Billy Bragg suggests in his excellent book on skiffle that this was a mishearing by Donegan of "Mule-ine", from one of Lead Belly's recordings -- and instead of having to wait "in the hole" -- wait at the side while another train goes past, the driver lies in order to avoid paying a toll (which wasn't a feature on American railways).

Amazingly, Donegan's version of the song's intro became the standard, even for American musicians who presumably had some idea of American geography or the workings of American railways. Here, for example, is the start of Johnny Cash's version from 1957:

[Excerpt: Johnny Cash "Rock Island Line"]

But it wasn't the story that made Donegan's version successful -- rather, it was the way it became a wailing, caterwauling, whirlwind of energy, unlike anything else ever previously recorded by a British musician, and far more visceral even than most American rock and roll records of the period.

[excerpt: Lonnie Donegan "Rock Island Line"]

"Rock Island Line" was originally put out as an album track on the Chris Barber album, but was released as a single under Donegan's name a year later, and shot to number one in the UK charts. But while it seemed like it was just a novelty hit at first, it soon became apparent that it was much more than that -- and it could be argued that, other than "Rock Around the Clock", it was the most important single record we've covered here. Because "Rock Island Line" created the skiffle craze, and without the skiffle craze everything would be totally different. Soon there were dozens of bands, up and down the country, playing whitebread versions of 1920s and 30s black American folk songs.

The thing about the skiffle craze was that, unlike every popular music format before -- and most since -- skiffle could be emulated by *anyone*. It helped if you had a guitar or a banjo, of course, or maybe a harmonica, but the other instruments that were typically used were made out of household items -- a washboard, played with a thimble; a teachest bass, made with a teachest and a broom handle; possibly a jug, or comb and paper.

(Of course, ironically, many of these things later became obsolete, and now the only place you're likely to find a washboard is in a music shop, being sold at an outrageously high price for people who want to play skiffle music).

This was in stark contrast to other musical genres. An electric guitar, or a piano, or a saxophone or trumpet or what have you, required a significant investment, money that most people simply didn't have.

Because one thing we've not mentioned yet, but which is hugely important here, is *just how poor* Britain was in 1954.

The USA was going through a post-war boom, because it was the only major industrialised nation in the world that hadn't had much of its industrial capacity destroyed in the war, and so it had become the world's salesman. If you wanted to buy consumer goods of any type, you bought American, because America still had factories, and it had people who could work in them rather than having to rebuild bombed-out cities. Much of the story of rock and roll ties in with this -- this is the time when America was in the ascendant as a world power.

The UK, on the other hand, had gone through two devastating wars in a forty-year period, and basically had to rebuild all its major cities from scratch. And it wasn't helped by the US suddenly, in August 1945. withdrawing all its help for Britain in what had been the Lend-Lease programme. 55% of the UK's GDP in the second world war had been devoted to the war, and it ended up having to take out a massive loan from the US to replace the previous aid it had been given. That loan was agreed in 1946, and the final instalment of it was paid in 2006.

The result of this economic hardship was that the post-war years were a time of terrible deprivation in the UK, to the extent that rationing only ended in July 1954 -- nine years after World War II ended, and a week before "Rock Island Line" was recorded.

(In fact, rationing in the UK ended on the same day that Elvis Presley recorded "That's All Right Mama", so if we want to draw a line in the sand and say "this is where the 1950s of the popular imagination, as opposed to the 1950s of the calendar, started", that would be as good a date as any to set).

Bear all this in mind as the story goes forward, and it'll explain a lot about British attitudes to America, in particular -- Britain looked to America with a combination of awe and envy, resentment and star-struck admiration, and a lot of that comes from the way that the two countries were developing economically during this time.

So, around the country, teenagers were looking for an outlet for their music, and they could easily see themselves as Lonnie Donegan, the lad from Scotland brought up in London. Half the teenagers in the country bought themselves guitars, or made basses out of teachests.

And Lonnie Donegan was even a big star in the US! All the music papers were saying so! Maybe, just maybe, it was possible for you to go and become famous in the US as well!

Because, surprisingly, Donegan's record did make the top ten in the pop charts in the USA, in what became the first example of a long line of white British men with guitars gaining commercial success in the US by selling the music of the US' own black people back to white teenagers. Donegan wasn't a big star over there, but he was close enough that the British music papers, buoyed by patriotism, could pretend he was.

In fact, Donegan wasn't quite a one-hit wonder in the USA -- he was a two-hit wonder, first with "Rock Island Line", and a few years later with the novelty song "Does Your Chewing Gum Lose Its Flavour On The Bedpost Overnight?" -- but he still made more of an impact there than any other British musician of his generation.

[excerpt: Lonnie Donegan “Does Your Chewing Gum Lose Its Flavour On The Bedpost Overnight?”]

Any version of "Rock Island Line" recorded by an American after 1955 would be based around Donegan's version. Bobby Darin's first single, for example, was a cover version of Donegan's record, in a reversal of the usual process which would involve British people copying the latest American hit for the domestic market. It was the first time since Ray Noble in the 1930s that a British musician had achieved any kind of level of popular success in the USA at all, and the British music public were proud of Donegan.

Except, that is, for the trad jazz fans who were Donegan's original audience. For a lot of them, Donegan was polluting the purity of the music. The trad jazz *musicians* usually didn't mind this. But the purists in the music papers really, really, disliked Donegan.

Not that credibility mattered -- after all, as the session guitarist Bert Weedon said to Donegan, "You’re the first man to have made any money out of the guitar. Bloody well done!" And while Donegan didn't make any more than his initial sixteen pound session fee -- his fee for the entire Chris Barber album from which "Rock Island Line" was taken -- from the initial recording, he did indeed become financially very successful from his follow-up hits like "Puttin' on the Style":

[Excerpt: Lonnie Donegan "Puttin' on the Style"]

That was famously parodied by Peter Sellers:

[excerpt: Peter Sellers "Puttin' on the Smile"]

But there's another recording of that song which probably shows its cultural impact better. This is a very, very, low-fidelity recording of a teenage skiffle group performing the song in 1957. Apologies for the poor quality, but it's frankly a miracle this survives at all:

[excerpt: The Quarrymen, "Puttin' on the Style"]

Later, on the same day that recording was made, the sixteen-year-old boy singing lead there would be introduced properly for the first time to another teenager, who he would invite to join his skiffle group. But it'll be a while yet before we talk about John Lennon and Paul McCartney properly.

Next Episodes

Crowdfunding Update -- Patreon and Kickstarter @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2019-02-25 03:52 / ⌛ 00:02:24

Crowdfunding Update — Patreon and Kickstarter @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2019-02-25 03:52

"Rock Around the Clock" by Bill Haley and the Comets @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2019-02-18 06:52 / ⌛ 00:35:44

“Rock Around the Clock” by Bill Haley and the Comets @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2019-02-18 06:52

"That's All Right, Mama" by Elvis Presley @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2019-02-11 03:11 / ⌛ 00:32:51