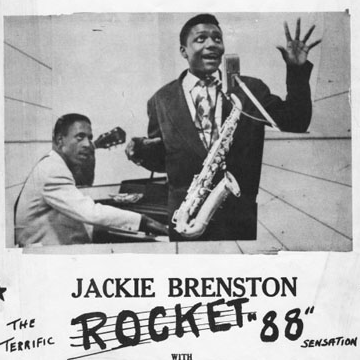

"Rocket 88" by Jackie Brenston and the Delta Cats

A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

Welcome to episode eleven of A History of Rock Music in Five Hundred Songs. Today we're looking at "Rocket 88" by Jackie Brenston and the Delta Cats. Click the full post to read liner notes, links to more information, and a transcript of the episode.

----more----

Resources

As always, I've created a Mixcloud streaming playlist with full versions of all the songs in the episode.

Both "Rocket 88" and the Howlin' Wolf tune used here are on Memphis Vol. 3 - Recordings from the Legendary Sun Studios, the third in a series of ludicrously cheap ten-CD box sets (this one currently selling on Amazon for £12!) which between them cover every single and B-side recorded in Sam Phillips' studio in the 1950s.

Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock 'n' Roll by Peter Guralnick is the definitive biography of Phillips. A content warning, though -- the book contains racial slurs, always in quoted speech and used to illustrate historical racism, but some may still find that upsetting.

Ike Turner wrote an autobiography, but I'm not going to recommend a book which exists solely to minimise his abuse of his wife. However, Turner was also interviewed by ghostwriter Kurt Loder for Tina Turner's autobiography I, Tina, and his description of the recording of "Rocket 88" is in there, so if you want to hear his take on the story, buy that.

Content Note

As you may have noticed from the above, this episode deals with Ike Turner, a man who is now as widely known for his spousal abuse as for his music. I mention this disclaimer episode in the podcast, and everything there goes for this episode. This episode is about the music, and about music he made before his horrific acts, but I don't want to give the impression I'm condoning or ignoring those.

Patreon

This podcast is brought to you by the generosity of my backers on Patreon. Why not join them?

Transcript

There is, of course, no actual "first rock and roll record", and if there is, it's not "Rocket 88". But nonetheless, "Rocket 88" has been officially anointed "the first rock and roll record ever made" by generations of white male music journalists, and so we need to talk about it. And it is, actually, quite a good record of its type, even if not especially innovative.

Before I talk about this, go and listen if you haven't already to the disclaimer episode I did after episode two (I'll link it in the show notes) about my attitudes towards misogynistic abusers who happen also to have played on some great records. I don't want to repeat all that here, but at the same time I definitely want to go on record that I'm not an admirer of Ike Turner. Because as it is, here at the official "beginning of rock" according to thousands of attempts to set a canon, we also have the beginning of rock being created by abusive men. Literally at the beginning in this case -- Ike Turner plays the opening piano part. And here we see how impossible it is to untangle the work of people like him from this history, as that piano part is one that would echo down the ages, becoming part of the bloodstream of popular music.

Anyway, enough about that.

To talk about "Rocket 88" we first have to talk about the Honeydrippers, and about the Liggins Brothers.

Joe Liggins was a piano player, with a small-time band called Sammy Franklin and the California Rhythm Rascals. In 1942, Liggins wrote a song called "The Honeydripper", which the California Rhythm Rascals used to perform quite regularly. It's a pleasant, enjoyable, boogie-flavoured jump band piece, which had a very catchy, unusual, riff, based loosely around the riff from "Shortenin' Bread". It was mostly just an excuse for soloing and extended improvisation -- sometimes it could last for fifteen minutes or more when performed live -- but it was surprisingly catchy nonetheless.

Liggins believed it had some commercial potential, so he went to his boss, Franklin, with a deal. He said he thought it could be a big hit, and they should make a record of it. If Sammy Franklin would pay $500 towards the cost of making the record, Liggins would give Franklin half the composer rights for the song.

Sammy Franklin turned him down, and Liggins believed in his song so much that he quit the band and formed his own jump band, which he named after the song. Eventually, three years later, Joe Liggins and the Honeydrippers went into the studio and recorded "The Honeydripper Parts 1 & 2" for a small indie label, Exclusive Records, and it was released in April 1945.

[Excerpt: "The Honeydripper" by Joe Liggins and the Honeydrippers]

It doesn't sound that much now -- pleasant enough, but hardly the most exceptional record ever. But that's with seventy-three years of hindsight. It went to number thirteen on the pop charts -- which is a remarkable feat for an R&B record in itself -- but its performance on the R&B charts was just ludicrous. It went to number one on the race charts (later the R&B charts) for eighteen weeks straight, from September 1945 through January 1946. The only reason it didn't stay at the top for longer was because the record label simply couldn't keep up with the demand, and it was replaced at number one by Louis Jordan, but at number two was Jimmie Lunceford playing... "The Honeydripper"

[Excerpt: Jimmie Lunceford's version of "The Honeydripper"].

At number three, meanwhile, was Roosevelt Sykes playing... "The Honeydripper". Later in 1946, Cab Calloway also had a number three hit with the song.

Joe Liggins and the Honeydrippers' version, alone, sold over two million copies in 1945 and 46, and it still, seventy-three years later, is joint holder of the title for longest stay at number one in the race or R&B charts ("Choo Choo Ch'Boogie" is the other joint holder, and that came a few months later). It's likely that nobody will ever beat that record. "The Honeydripper" was a sensation.

Meanwhile the California Rhythm Rascals had renamed themselves Sammy Franklin and his Atomics, in an attempt to sound more up to date and modern, with the atomic bomb having so recently gone off. They recorded their own version of "The Honeydripper". It sank without trace -- but you'll remember from last week that that record launched the production career of Ralph Bass. "The Honeydripper" made money and careers for everyone in the music industry, except for Sammy Franklin.

Sammy Franklin may not have been the single most unwise person in the history of rock and roll -- he didn't turn down Elvis or quit the Beatles or anything like that -- but still, one has to imagine that he spent the whole rest of his life regretting that he hadn't just spent that five hundred dollars.

Joe Liggins never had another success as big as "The Honeydripper", but he had a few minor successes to go along with it, and that was enough for him to give his brother Jimmy a job as the band's driver -- at that time, it was *very* rare for bands to have actual employees, rather than doing their own driving and carrying their own instruments, and for Jimmy it was certainly an improvement on his previous career as a boxer under the name Kid Zulu.

But Jimmy also played a bit of guitar, and so he decided, inspired by his brother's success, to try his hand at his own music career, and he formed his own jump band, the Drops of Joy.

The Drops of Joy signed up to Specialty Records, a label we'll be hearing a *lot* about in upcoming episodes. But the Drops of Joy would normally not be a band that we'd be talking about. They weren't the most imaginative or innovative band by a long way, and they only had minor hits. Their songs were mostly generic boogies, called things like "Saturday Night Boogie Woogie Man" or "Night Life Boogie" -- all perfectly good music of its type, but nothing that set the world on fire.

But one B-side, "Cadillac Boogie" was, indirectly, responsible for a great deal of the music that would follow...

[Excerpt "Cadillac Boogie" by Jimmy Liggins and the Drops of Joy]

To see why "Cadillac Boogie" was a big influence, we now need to turn to Sam Phillips. It's safe to say that he's one of the two or three most important people in the history of rock and roll music -- and it's also safe to say that even if rock and roll had never happened at all, we'd still be talking about Sam Phillips because of his influence on country and blues music. He may well have been the single most important record producer of the 1950s -- he's as important to the history of American music as anyone who ever lived.

Phillips had started out as a DJ, but had moved sideways from there into recording bands for radio sessions. He had very strong opinions about the way things should sound, and he was willing to work hard to get the sound the way he wanted it. In particular, when he recorded big bands for sessions, he would mic the rhythm section far more than was traditional -- when you heard a big band recorded by Sam Phillips, you could hear the guitar and the bass in a way you couldn't when you heard that band on the records.

He had a real ear for sound, but he also had an ear for *performance*.

Like a lot of the men we're dealing with at this point, Sam Phillips was a white man who was motivated by a deeply-felt anger at racial injustice, which expressed itself as a belief that if other white people could just see the humanity, and the talent, in black people the way he could, the world would be a much better place. The racial attitudes of people like him can seem a little patronising these days, as if the problems in America were just down to a few people's feelings, and if those feelings could be changed everything would be better, but given the utterly horrendous attitudes expressed by the people around him, Phillips was at least partly right -- if he could get his fellow white people to just stop being vicious towards black people, well, that wouldn't fix all the problems by any means, but it would have been a good start.

He was also someone who was very much of the opinion that if a problem needed fixing, he should try to fix it himself. During the Cuban missile crisis he decided that since Castro seemed a reasonable sort of person and a good progressive like Phillips himself, the whole thing could be sorted out if a decent American just had a one-to-one chat with him. And since no-one else was doing that, he decided he might as well do it himself. So he phoned Cuba, and while he couldn't get through to Fidel Castro himself, he did get through to Castro's brother Raul, and had a long conversation with him. History does not relate whether it was Sam Phillips' intervention that saved the world from nuclear war.

And what Sam Phillips thought he could do to stop the evil of racism -- and also to improve the world in other ways -- was to capture the music that the black people he saw around him in Memphis were making. The world seemed to him to be full of talented, idiosyncratic, people who were making music like nothing else he had heard.

And so he started Memphis Recording Services, with the help of his mistress Marion Keisker, who acted as his assistant and was herself a popular radio presenter. Both kept their jobs at the radio station while starting the business, and they tried to get the business on a sound financial footing by recording things like weddings and funerals (yes, funerals, they'd mic up the funeral home and get a recording of the service which they'd put on an acetate disc -- apparently this was a popular service).

But the real purpose of the business was to be somewhere where real musicians could come and record. Phillips didn't have a record label, but he had arrangements with a couple of small labels to send them recordings, and sometimes those labels would put the recordings out. Musicians of all kinds would come into Memphis Recording Services, and Phillips would spend hours trying to get their sound onto disc and, later, tape. Not trying to perfect it, but trying to get the most authentic version of that person's artistry onto the tape.

In 1951 Memphis Recording Services hadn't been open that long, and Phillips had barely recorded anything worth a listen -- but he *had* made some recordings with a local DJ called Riley King, who had recently started going by the name "Blues Boy", or just "B.B." for short. To my mind they're actually some of King's best material -- much more my kind of thing than the later recordings that made his name. Here, for example, is one of those recordings that wasn't released at the time, but has made compilations later -- "Pray For You":

[excerpt: B.B. King "Pray For You"]

That was the kind of music that Sam Phillips liked, and it's the kind of thing I like too. The piano player there, incidentally, was a young man called Johnny Ace, about whom we'll hear a lot more later.

A couple of years earlier, King had met a young musician in Clarksdale Mississippi called Ike Turner, who led a big band called the Top Hatters. Turner had sat in with King on the piano and had impressed King with his ability, and King had even stopped over a couple of nights at Turner's house. The two hadn't stayed in touch, but they both liked each other.

The Top Hatters had later split up into two bands -- there was the Dukes of Swing, who played classy big band music, and the Kings of Rhythm, who were a jump band after the Louis Jordan fashion, led by Turner. One day, the Kings of Rhythm were coming back from a gig when they noticed a large number of cars parked outside a venue which had a poster advertising one "B.B. King". Ike Turner had noticed that name on posters before, but didn't know who it was, but thought he should check out why there were so many people wanting to see him.

The band stopped and went inside, and discovered that B.B. King was Ike Turner's old acquaintance Riley. Turner asked King if his band could get up and play a number, and King let him, and was hugely impressed, telling Turner that he should make records. Turner said he'd like to, but he had no idea how one actually went about making a record.

King said that the way he did it was there was a guy in Memphis called Sam who recorded him. King would call Sam up and tell him to give Turner a call on Monday. Monday came around, and indeed Sam Phillips did call Ike Turner on the telephone, and asked when they could come up to record. "Straight away", Ike replied, and they set off -- five men, two saxes, a guitar, and a drum kit in a single car, with the guitar amp and bass drum strapped to the roof.

The drive from Mississippi to Memphis was not without incident -- they got arrested and fined, ostensibly for a traffic violation but actually for being black in the deep South, and they also got a flat tyre, and when they changed it the guitar amp fell on the road.

At least, that's one story as to what happened to the guitar amp -- like everything when it comes to this music, there are three or four different stories told by different people, but that's definitely one of them.

Anyway, when they got to the studio, and got their gear set up, the amplifier made a strange sound. The band were horrified -- their big break, and it was all going to be destroyed because their amp was making this horrible dirty sound. The speaker cone had been damaged.

Sam Phillips, however, was very much not horrified. He was delighted. He got some brown paper from the restaurant next door to stuff inside as a temporary repair, but said that the damaged amp would sound different, and different, to Sam Phillips at least, was always good.

The song they chose to record that day was one that was written by the saxophone player, Jackie Brenston.

Well, I say written by… as with so many of the songs we've seen here, the song was not so much written as remembered (as indeed that line is -- I remembered it from Leslie Halliwell, talking about Talbot Rothwell's scripts for the Carry On films, so I thought I should give it credit here). Specifically, he was remembering "Cadillac Boogie", as you can tell if you listen to it for even a few seconds:

[insert a chunk of Rocket 88]

Now the main difference in the songwriting is simply the car that's being talked about -- the 88 was a new, exciting, model, and Brenston made the song more hip and current as a result. But *musically* there are a few things of note here.

Firstly, there's the piano part, written and played by Ike Turner -- that part is one that Little Richard adored, to the point that he copied it on the intro to “Good Golly Miss Molly”. Compare and contrast; here's the intro to “Rocket 88”:

[intro to Rocket 88]

and here's Little Richard playing “Good Golly Miss Molly”:

[intro to Good Golly Miss Molly]

There's another difference as well -- the guitar sound. There's distortion all over it, thanks to that cone.

Now, this probably won't even have been something that anyone listening at the time noticed -- if you're listening in the context of early fifties R&B, on the poor-quality 78 RPM discs that the music was released on, you'd probably think that buzzing boogie line was a baritone sax -- the line it's playing is the kind of thing that a horn would normally play, and the distortion sounds the same way as many of the distorted sax lines at the time did. But that was enough that when white music critics in the seventies were looking for a "first rock and roll record", they latched on to this one -- because in the seventies rock and roll *meant* distorted guitar.

When the record came out, Ike Turner was horrified -- because he'd assumed it would be released as by Ike Turner and his Kings of Rhythm, but instead it was under the name "Jackie Brenston and his Delta Cats". And the record was successful enough to make Jackie Brenston decide to quit the Kings of Rhythm and go solo. He released a few more singles, mostly along the same lines as Rocket 88, but they did nothing.

Brenston's solo career fizzled out quite quickly, and he joined the backing band for Lowell Fulson, the blues star. After a couple of years with Fulson, he returned to play with Ike Turner's band. He stayed with Turner from 1955 through 1962, a sideman once more, and Turner wouldn't let Brenston sing his hit on stage -- he was never going to be upstaged by his sax player again.

Eventually Jackie Brenston became an alcoholic, and from 1963 until his death in 1979, he worked as a part-time truck driver, never seeing any recognition for his part in starting rock and roll.

But "Rocket 88" had repercussions for a lot of other people, even if it was only a one-off hit for Brenston. For Ike Turner, after "Rocket 88" was released, half of his band quit and stayed with Brenston, so for a long time he was without a full band. He started to work for Phillips as a talent scout and musician, and it was Turner who brought Phillips several artists, including the artist who Phillips later claimed was the greatest artist and greatest human being he ever worked with -- Howlin' Wolf.

[excerpt "How Many More Years" -- version from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1lTpcKnp-NQ ]

That's a recording that was made at Phillips' studio, with Turner on piano. Phillips licensed several singles by Howlin' Wolf and others to Chess Records, but then the Chess brothers, the owners of that label, used contractual shenanigans to cut Phillips out of the loop and record the Wolf directly. So Phillips made a resolution to start his own record label, where no-one would steal his artists. Sun Records was born out of this frustration. Meanwhile, Ike Turner resolved that he would never again see his name removed from the credits for a record he was on. When he got a new Kings of Rhythm together, he switched from playing piano, where you're sat at the side of the stage, to playing guitar, where you can be up front and in the spotlight And when the Kings of Rhythm got a new singer, Annie-Mae Bullock, Turner made sure he would always have equal billing, by giving her his surname as a stage name, so any records she made would be by the new act, "Ike and Tina Turner".

And finally, "Rocket 88" was going to have a profound effect on the career of one man who would later make a big difference to rock and roll. The lead singer of the country band the Saddlemen -- a singer who was best known as a champion yodeller -- was also working as a DJ for a small Pennsylvania station, and he noticed that Louis Jordan records were popular among the country audience, and he decided to start incorporating a Louis Jordan style in his own music

But Jordan's records were so popular with a crossover audience that when the Saddlemen came to make their first records in this new style, they chose to cover something by someone other than Jordan – someone that hadn't crossed over into the country market yet. And so they chose to record "Rocket 88", which had been a big R&B hit but hadn't broken through into the white audience. Their version of the song is *also* credited by some as the first rock and roll record. But it'll be a few weeks until Bill Haley becomes a full part of our story...

Next Episodes

"Double Crossin' Blues", by Johnny Otis, Little Esther, and the Robins @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2018-12-10 00:21 / ⌛ 00:30:02

"How High The Moon" by Les Paul and Mary Ford @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2018-12-03 05:40 / ⌛ 00:28:15

“How High The Moon” by Les Paul and Mary Ford @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2018-12-03 05:40

"The Fat Man" by Fats Domino @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2018-11-26 01:06 / ⌛ 00:29:38