Episode 58: “Mr. Lee” by the Bobbettes

A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

Episode fifty-eight of A History of Rock Music in Five Hundred Songs looks at “Mr. Lee” by the Bobbettes, and at the lbirth of the girl group sound. Click the full post to read liner notes, links to more information, and a transcript of the episode.

Patreon backers also have a ten-minute bonus episode available, on “Little Bitty Pretty One”, by Thurston Harris.

—-more—-

Resources

As always, I’ve created a Mixcloud streaming playlist with full versions of all the songs in the episode.

I’ve used multiple sources to piece together the information here.

Marv Goldberg’s page is always the go-to for fifties R&B groups.

Girl Groups: Fabulous Females Who Rocked the World by John Clemente has an article about the group with some interview material.

American Singing Groups by Jay Warner also has an article on the group.

Most of the Bobbettes’ material is out of print, but handily this CD is coming out next Friday, with most of their important singles on it. I have no idea of its quality, as it’s not yet out, but it seems like it should be the CD to get if you want to hear more of their music.

Patreon

This podcast is brought to you by the generosity of my backers on Patreon. Why not join them?

Transcript

Over the last few months we’ve seen the introduction to rock and roll music of almost all the elements that would characterise the music in the 1960s — we have the music slowly standardising on a lineup of guitar, bass, and drums, with electric guitar lead. We have the blues-based melodies, the backbeat, the country-inspired guitar lines. All of them are there. They just need putting together in precisely the right proportions for the familiar sound of the early-sixties beat groups to come out.

But there’s one element, as important as all of these, which has not yet turned up, and which we’re about to see for the first time. And that element is the girl group.

Girl groups played a vital part in the development of rock and roll music, and are never given the credit they deserve. But you just have to look at the first Beatles album to see how important they were. Of the six cover versions on “Please Please Me”, three are of songs originally recorded by girl groups — two by the Shirelles, and one by the Cookies.

And the thing about the girl groups is that they were marketed as collectives, not as individuals — occasionally the lead singer would be marketed as a star in her own right, but more normally it would be the group, not the members, who were known.

So it’s quite surprising that the first R&B girl group to hit the charts was one that, with the exception of one member, managed to keep their original members until they died. and where two of those members were still in the group into the middle of the current decade.

So today, we’re going to have a look at the group that introduced the girl group sound to rock and roll, and how the world of music was irrevocably changed because of how a few young kids felt about their fifth-grade teacher.

[Excerpt: The Bobettes, “Mister Lee”]

Now, we have to make a distinction here when we’re talking about girl groups. There had, after all, been many vocal groups in the pre-rock era that consisted entirely of women — the Andrews Sisters, for example, had been hugely popular, as had the Boswell Sisters, who sang the theme song to this show.

But those groups were mostly what was then called “modern harmony” — they were singing block harmonies, often with jazz chords, and singing them on songs that came straight from Tin Pan Alley. There was no R&B influence in them whatsoever.

When we talk about girl groups in rock and roll, we’re talking about something that quickly became a standard lineup — you’d have one woman out front singing the lead vocal, and two or three others behind her singing answering phrases and providing “ooh” vocals. The songs they performed would be, almost without exception, in the R&B mould, but would usually have much less gospel influence than the male vocal groups or the R&B solo singers who were coming up at the same time. While doo-wop groups and solo singers were all about showing off individual virtuosity, the girl groups were about the group as a collective — with very rare exceptions, the lead singers of the girl groups would use very little melisma or ornamentation, and would just sing the melody straight.

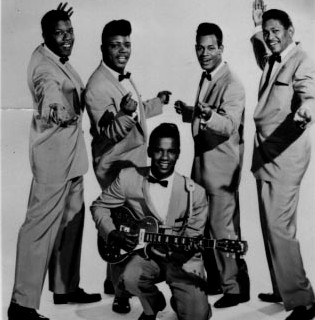

And when it comes to that kind of girl group, the Bobbettes were the first one to have any real impact.

They started out as a group of children who sang after school, at church and at the glee club. The same gang of seven kids, aged between eleven and fifteen, would get together and sing, usually pop songs. After a little while, though, Reather Dixon and Emma Pought, the two girls who’d started this up, decided that they wanted to take things a bit more seriously. They decided that seven girls was too many, and so they whittled the numbers down to the five best singers — Reather and Emma, plus Helen Gathers, Laura Webb, and Emma’s sister Jannie.

The girls originally named themselves the Harlem Queens, and started performing at talent shows around New York.

We’ve talked before about how important amateur nights were for black entertainment in the forties and fifties, but it’s been a while, so to refresh your memories — at this point in time, black live entertainment was dominated by what was known as the Chitlin Circuit, an informal network of clubs and theatres around the US which put on largely black acts for almost exclusively black customers. Those venues would often have shows that lasted all day — a ticket for the Harlem Apollo, for example, would allow you to come and go all day, and see the same performers half a dozen times. To fill out these long bills, as well as getting the acts to perform multiple times a day, several of the chitlin circuit venues would put on talent nights, where young performers could get up on stage and have a chance to win over the audiences, who were notoriously unforgiving.

Despite the image we might have in our heads now of amateur talent nights, these talent contests would often produce some of the greatest performers in the music business, and people like Johnny Otis would look to them to discover new talent. They were a way for untried performers to get themselves noticed, and while few did, some of those who managed would go on to have great success.

And so in late 1956, the five Harlem Queens, two of them aged only eleven, went on stage at the Harlem Apollo, home of the most notoriously tough audiences in America.

But they went down well enough that James Dailey, the manager of a minor bird group called the Ospreys, decided to take them on as well. The Ospreys were a popular group around New York who would eventually get signed to Atlantic, and release records like “Do You Wanna Jump Children”:

[Excerpt: The Ospreys, “Do You Wanna Jump Children?”]

Dailey thought that the Harlem Queens had the potential to be much bigger than the Ospreys, and he decided to try to get them signed to Atlantic Records. But one thing would need to change — the Harlem Queens sounded more like a motorcycle gang than the name of a vocal group.

Laura’s sister had just had a baby, who she’d named Chanel Bobbette. They decided to name the group after the baby, but the Chanels sounded too much like the Chantels, a group from the Bronx who had already started performing. So they became the Bobbettes.

They signed to Atlantic, where Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler encouraged them to perform their own material. The girls had been writing songs together, and they had one — essentially a playground chant — that they’d been singing together for a while, about their fifth-grade teacher Mr. Lee. Depending on who you believe — the girls gave different accounts over the years — the song was either attacking him, or merely affectionately mocking his appearance. It called him “four-eyed” and said he was “the ugliest teacher you ever did see”.

Atlantic liked the feel of the song, but they didn’t want the girls singing a song that was just attacking a teacher, and so they insisted on them changing the lyrics. With the help of Reggie Obrecht, the bandleader for the session, who got a co-writing credit on the song largely for transcribing the girls’ melody and turning it into something that musicians could play, the song became, instead, a song about “the handsomest sweetie you ever did see”:

[Excerpt: The Bobbettes, “Mister Lee”]

Incidentally, there seems to be some disagreement about who the musicians were on the track. Jacqueline Warwick, in “Girl Groups, Girl Culture”, claims that the saxophone solo on “Mr. Lee” was played by King Curtis, who did play on many sessions for Atlantic at the time. It’s possible — and Curtis was an extremely versatile player, but he generally played with a very thick tone. Compare his playing on “Dynamite at Midnight”, a solo track he released in 1957:

[Excerpt: King Curtis, “Dynamite at Midnight”]

With the solo on “Mr Lee”:

[Excerpt: The Bobbettes, “Mister Lee”]

I think it more likely that the credit I’ve seen in other places, such as Atlantic sessionographies, is correct, and that the sax solo is played by the less-well-known player Jesse Powell, who played on, for example, “Fools Fall in Love” by the Drifters:

[Excerpt: The Drifters, “Fools Fall In Love”]

If that’s correct — and my ears tell me it is — then presumably the other credits in those sources are also correct, and the backing for “Mister Lee” was mostly provided by B-team session players, the people who Atlantic would get in for less important sessions, rather than the first-call people they would use on their major artists — so the musicians were Jesse Powell on tenor sax; Ray Ellis on piano; Alan Hanlon and Al Caiola on guitar; Milt Hinton on bass; and Joe Marshall on drums.

“Mr. Lee” became a massive hit, going to number one on the R&B charts and making the top ten on the pop charts, and making the girls the first all-girl R&B vocal group to have a hit record, though they would soon be followed by others — the Chantels, whose name they had tried not to copy, charted a few weeks later.

“Mr. Lee” also inspired several answer records, most notably the instrumental “Walking with Mr. Lee” by Lee Allen, which was a minor hit in 1958, thanks largely to it being regularly featured on American Bandstand:

[Excerpt: Lee Allen, “Walking With Mr. Lee”]

The song also came to the notice of their teacher — who seemed to have already known about the girls’ song mocking him. He called a couple of the girls out of their class at school, and checked with them that they knew the song had been made into a record. He’d recognised it as the song the girls had sung about him, and he was concerned that perhaps someone had heard the girls singing their song and stolen it from them. They explained that the record was actually them, and he was, according to Reather Dixon, “ecstatic” that the song had been made into a record — which suggests that whatever the girls’ intention with the song, their teacher took it as an affectionate one.

However, they didn’t stay at that school long after the record became a hit. The girls were sent off on package tours of the Chitlin’ circuit, touring with other Atlantic artists like Clyde McPhatter and Ruth Brown, and so they were pulled out of their normal school and started attending The Professional School For Children, a school in New York that was also attended by Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers and the Chantels, among others, which would allow them to do their work while on tour and post it back to the school.

On the tours, the girls were very much taken under the wing of the adult performers. Men like Sam Cooke, Clyde McPhatter, and Jackie Wilson would take on somewhat paternal roles, trying to ensure that nothing bad would happen to these little girls away from home, while women like Ruth Brown and LaVern Baker would teach them how to dress, how to behave on stage, and what makeup to wear — something they had been unable to learn from their male manager.

Indeed, their manager, James Dailey, had started as a tailor, and for a long time sewed the girls’ dresses himself — which resulted in the group getting a reputation as the worst-dressed group on the circuit, one of the reasons they eventually dumped him.

With “Mr. Lee” a massive success, Atlantic wanted the group to produce more of the same — catchy upbeat novelty numbers that they wrote themselves. The next single, “Speedy”, was very much in the “Mr. Lee” style, but was also a more generic song, without “Mr. Lee”‘s exuberance:

[Excerpt: The Bobbettes, “Speedy”]

One interesting thing here is that as well as touring the US, the Bobbettes made several trips to the West Indies, where R&B was hugely popular. The Bobbettes were, along with Gene and Eunice and Fats Domino, one of the US acts who made an outsized impression, particularly in Jamaica, and listening to the rhythms on their early records you can clearly see the influence they would later have on reggae. We’ll talk more about reggae and ska in future episodes, but to simplify hugely, the biggest influences on those genres as they were starting in the fifties were calypso, the New Orleans R&B records made in Cosimo Matassa’s studio, and the R&B music Atlantic was putting out, and the Bobbettes were a prime part of that influence.

“Mr. Lee”, in particular, was later recorded by a number of Jamaican reggae artists, including Laurel Aitken:

[Excerpt: Laurel Aitken, “Mr. Lee”]

And the Harmonians:

[Excerpt: the Harmonians, “Music Street”]

But while “Mr Lee” was having a massive impact, and the group was a huge live act, they were becoming increasingly dissatisfied with the way their recording career was going. Atlantic was insisting that they keep writing songs in the style of “Mr. Lee”, but they were so busy they were having to slap the songs together in a hurry rather than spend time working on them, and they wanted to move on to making other kinds of records, especially since all the “Mr. Lee” soundalikes weren’t actually hitting the charts.

They were also trying to expand by working with other artists — they would often act as the backing vocalists for other acts on the package shows they were on, and I’ve read in several sources that they performed uncredited backing vocals on some records for Clyde McPhatter and Ivory Joe Hunter, although nobody ever says which songs they sang on. I can’t find an Ivory Joe Hunter song that fits the bill during the Bobbettes’ time on Atlantic, but I think “You’ll Be There” is a plausible candidate for a Clyde McPhatter song they could have sung on — it’s one of the few records McPhatter made around this time with obviously female vocals on it, it was arranged and conducted by Ray Ellis, who did the same job on the Bobbettes’ records, and it was recorded only a few days after a Bobbettes session. I can’t identify the voices on the record well enough to be convinced it’s them, but it could well be:

[Excerpt: Clyde McPhatter, “You’ll Be There”]

Eventually, after a couple of years of frustration at their being required to rework their one hit, they recorded a track which let us know how they really felt:

[Excerpt: The Bobbettes, “I Shot Mr. Lee”, Atlantic version]

I think that expresses their feelings pretty well. They submitted that to Atlantic, who refused to release it, and dropped the girls from their label. This started a period where they would sign with different labels for one or two singles, and would often cut the same song for different labels. One label they signed to, in 1960, was Triple-X Records, one of the many labels run by George Goldner, the associate of Morris Levy we talked about in the episode on “Why Do Fools Fall In Love”, who was known for having the musical taste of a fourteen-year-old girl. There they started what would be a long-term working relationship with the songwriter and producer Teddy Vann.

Vann is best known for writing “Love Power” for the Sand Pebbles:

[Excerpt: The Sand Pebbles, “Love Power”]

And for his later minor novelty hit, “Santa Claus is a Black Man”:

[Excerpt: Akim and Teddy Vann, “Santa Claus is a Black Man”]

But in 1960 he was just starting out, and he was enthusiastic about working with the Bobbettes. One of the first things he did with them was to remake the song that Atlantic had rejected, “I Shot Mr. Lee”:

[Excerpt: The Bobbettes, “I Shot Mr. Lee”, Triple-X version]

That became their biggest hit since the original “Mr. Lee”, reaching number fifty-two on the Billboard Hot One Hundred, and prompting Atlantic to finally issue the original version of “I Shot Mr. Lee” to compete with it.

There were a few follow-ups, which also charted in the lower regions of the charts, most of them, like “I Shot Mr. Lee”, answer records, though answers to other people’s records. They charted with a remake of Billy Ward and the Dominos’ “Have Mercy Baby”, with “I Don’t Like It Like That”, an answer to Chris Kenner’s “I Like It Like That”, and finally with “Dance With Me Georgie”, a reworking of “The Wallflower” that referenced the then-popular twist craze.

[Excerpt: The Bobbettes, “Dance With Me Georgie”]

The Bobbettes kept switching labels, although usually working with Teddy Vann, for several years, with little chart success. Helen Gathers decided to quit — she stopped touring with the group in 1960, because she didn’t like to travel, and while she continued to record with them for a little while, eventually she left the group altogether, though they remained friendly. The remaining members continued as a quartet for the next twenty years.

While the Bobbettes didn’t have much success on their own after 1961, they did score one big hit as the backing group for another singer, when in 1964 they reached number four in the charts backing Johnny Thunder on “Loop De Loop”:

[Excerpt: Johnny Thunder, “Loop De Loop”]

The rest of the sixties saw them taking part in all sorts of side projects, none of them hugely commercially successful, but many of them interesting in their own right. Probably the oddest was a record released in 1964 to tie in with the film Dr Strangelove, under the name Dr Strangelove and the Fallouts:

[Excerpt: Dr Strangelove and the Fallouts, “Love That Bomb”]

Reather and Emma, the group’s two strongest singers, also recorded one single as the Soul Angels, featuring another singer, Mattie LaVette:

[Excerpt: The Soul Angels, “It’s All In Your Mind”]

The Bobbettes continued working together throughout the seventies, though they appear to have split up, at least for a time, around 1974. But by 1977, they’d decided that twenty years on from “Mister Lee”, their reputation from that song was holding them back, and so they attempted a comeback in a disco style, under a new name — the Sophisticated Ladies.

[Excerpt: Sophisticated Ladies, “Check it Out”]

That got something of a cult following among disco lovers, but it didn’t do anything commercially, and they reverted to the Bobbettes name for their final single, “Love Rhythm”:

[Excerpt: The Bobbettes, “Love Rhythm”]

But then, tragedy struck — Jannie Pought was stabbed to death in the street, in a random attack by a stranger, in September 1980. She was just thirty-four. The other group members struggled on as a trio.

Throughout the eighties and nineties, the group continued performing, still with three original members, though their performances got fewer and fewer. For much of that time they still held out hope that they could revive their recording career, and you see them talking in interviews from the eighties about how they were determined eventually to get a second gold record to go with “Mr. Lee”.

They never did, and they never recorded again — although they did eventually get a *platinum* record, as “Mr. Lee” was used in the platinum-selling soundtrack to the film Stand By Me.

Laura Webb Childress died in 2001, at which point the two remaining members, the two lead singers of the group, got in a couple of other backing vocalists, and carried on for another thirteen years, playing on bills with other fifties groups like the Flamingos, until Reather Dixon Turner died in 2014, leaving Emma Pought Patron as the only surviving member. Emma appears to have given up touring at that point and retired.

The Bobbettes may have only had one major hit under their own name, but they made several very fine records, had a career that let them work together for the rest of their lives, and not only paved the way for every girl group to follow, but also managed to help inspire a whole new genre with the influence they had over reggae. Not bad at all for a bunch of schoolgirls singing a song to make fun of their teacher…

Next Episodes

Episode 57: "Flying Saucers Rock 'n' Roll" by Billy Lee RIley @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2019-11-18 10:57 / ⌛ 00:37:09

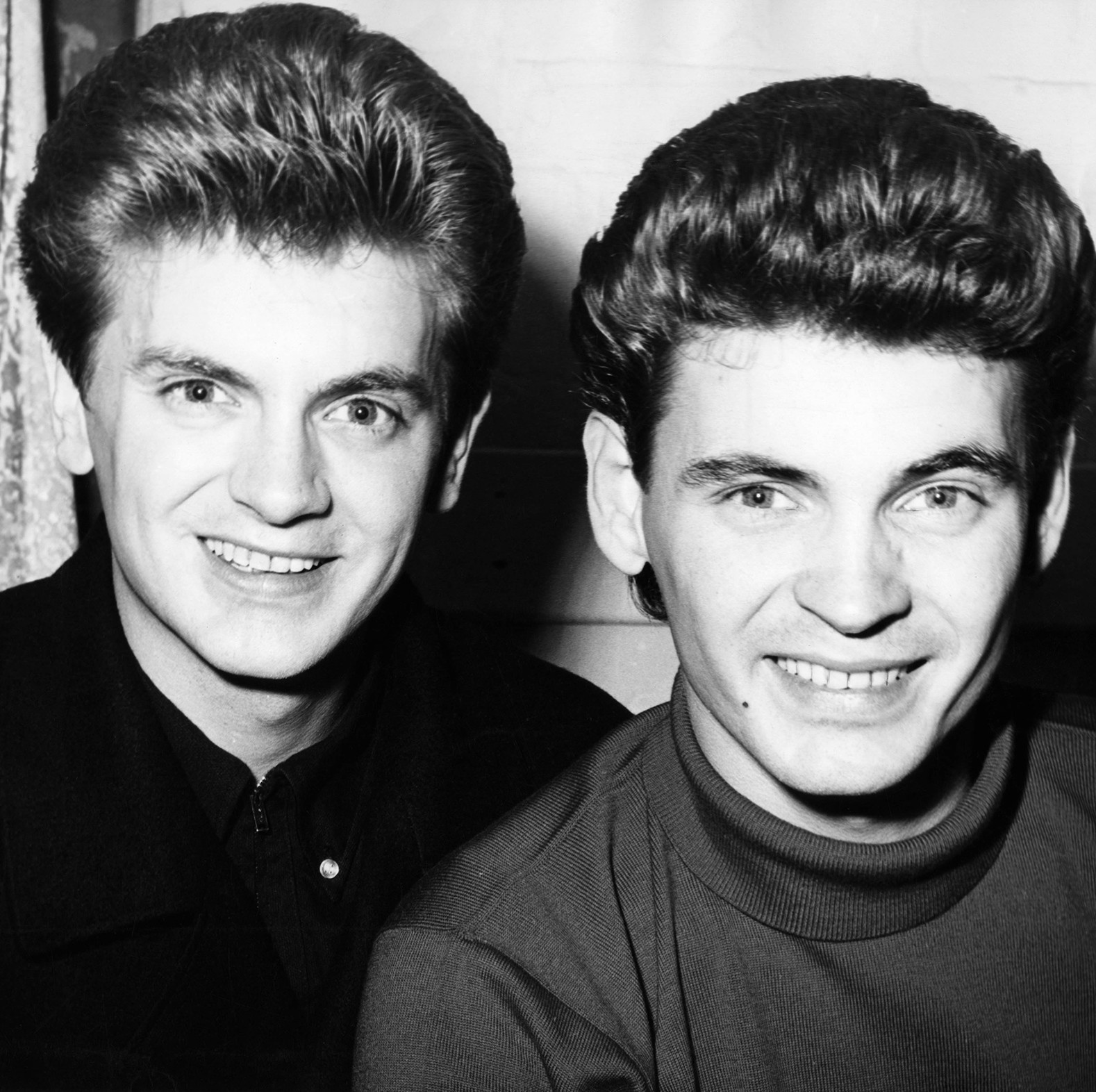

Episode 56: "Bye Bye Love" by the Everly Brothers @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2019-11-11 06:11 / ⌛ 00:36:36

Episode 56: “Bye Bye Love” by the Everly Brothers @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2019-11-11 06:11

Episode 55: "Searchin'" by the Coasters @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2019-11-04 10:34 / ⌛ 00:34:13