Episode 54: Keep A Knockin

A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

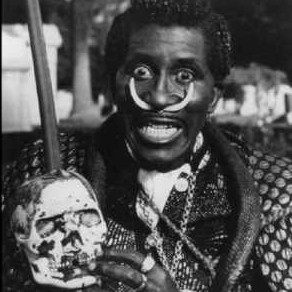

Episode fifty-four of A History of Rock Music in Five Hundred Songs looks at “Keep A Knockin'” by Little Richard, the long history of the song, and the tension between its performer’s faith and sexuality. Click the full post to read liner notes, links to more information, and a transcript of the episode.

Patreon backers also have a ten-minute bonus episode available, on “At the Hop” by Danny and the Juniors.

—-more—-

Resources

As always, I’ve created a Mixcloud streaming playlist with full versions of all the songs in the episode.

Most of the information used here comes from The Life and Times of Little Richard: The Authorised Biography by Charles White, which is to all intents and purposes Richard’s autobiography, as much of the text is in his own words. A warning for those who might be considering buying this though — it contains descriptions of his abuse as a child, and is also full of internalised homo- bi- and trans-phobia.

This collection contains everything Richard released before 1962, from his early blues singles through to his gospel albums from after he temporarily gave up rock and roll for the church.

Patreon

This podcast is brought to you by the generosity of my backers on Patreon. Why not join them?

Erratum

In the podcast I refer to a jazz band as “the Buddy Bolden Legacy Group”. Their name is actually “the Buddy Bolden Legacy Band”.

Transcript

When last we looked at Little Richard properly, he had just had a hit with “Long Tall Sally”, and was at the peak of his career. Since then, we’ve seen that he had become big enough that he was chosen over Fats Domino to record the theme tune to “The Girl Can’t Help It”, and that he was the inspiration for James Brown. But today we’re going to look in more detail at Little Richard’s career in the mid fifties, and at how he threw away that career for his beliefs.

[Excerpt: Little Richard with his Band, “Keep A Knockin'”]

Richard’s immediate follow-up to “Long Tall Sally” was another of his most successful records, a double-sided hit with both songs credited to John Marascalco and Bumps Blackwell — “Rip it Up” backed with “Ready Teddy”. These both went to number one on the R&B charts, but they possibly didn’t have quite the same power as RIchard’s first two singles. Where the earlier singles had been truly unique artefacts, songs that didn’t sound like anything else out there, “Rip it Up” and “Ready Teddy” were both much closer to the typical songs of the time — the lyrics were about going out and having a party and rocking and rolling, rather than about sex with men or cross-dressing sex workers.

But this didn’t make Richard any less successful, and throughout 1956 and 57 he kept releasing more hits, often releasing singles where both the A and B side became classics — we’ve discussed “The Girl Can’t Help It” and “She’s Got It” in the episode on “Twenty Flight Rock”, but there was also “Jenny Jenny”, “Send Me Some Lovin'”, and possibly the greatest of them all, “Lucille”:

[Excerpt: Little Richard, “Lucille”]

But Richard was getting annoyed at the routine of recording — or more precisely, he was getting annoyed at the musicians he was having to work with in the studio. He was convinced that his own backing band, the Upsetters, were at least as good as the studio musicians, and he was pushing for Specialty to let him use them in the studio.

And when they finally let him use the Upsetters in the studio, he recorded a song which had roots which go much further back than you might imagine.

“Keep A Knockin'” had a long, long, history. It derives originally from a piece called “A Bunch of Blues”, written by J. Paul Wyer and Alf Kelly in 1915. Wyer was a violin player with W.C. Handy’s band, and Handy recorded the tune in 1917:

[Excerpt: W.C. Handy’s Memphis Blues Band, “A Bunch of Blues”]

That itself, though, may derive from another song, “My Bucket’s Got A Hole in It”, which is an old jazz standard. There are claims that it was originally played by the great jazz trumpeter Buddy Bolden around the turn of the twentieth century. No recordings survive of Bolden playing the song, but a group called “the Buddy Bolden Legacy Group” have put together what, other than the use of modern recording, seems a reasonable facsimile of how Bolden would have played the song:

[Excerpt: “My Bucket’s Got a Hole in it”, the Buddy Bolden Legacy Band]

If Bolden did play that, then the melody dates back to around 1906 at the latest, as from 1907 on Bolden was in a psychiatric hospital with schizophrenia, but the 1915 date for “A Bunch of Blues” is the earliest definite date we have for the melody.

“My Bucket’s Got a Hole in it” would later be recorded by everyone from Hank Williams to Louis Armstrong, Jimmy Page and Robert Plant to Willie Nelson and Wynton Marsalis. It was particularly popular among country singers:

[Excerpt: Hank Williams, “My Bucket’s Got A Hole In It”]

But the song took another turn in 1928, when it was recorded by Tampa Red’s Hokum Jug Band. This group featured Tampa Red, who would later go on to be a blues legend in his own right, and “Georgia Tom”, who as Thomas Dorsey would later be best known as the writer of much of the core repertoire of gospel music. You might remember us talking about Dorsey in the episode on Rosetta Tharpe. He’s someone who wrote dirty, funny, blues songs until he had a religious experience while on stage, and instead became a writer of religious music, writing songs like “Precious Lord, Take My Hand” and “Peace in the Valley”.

But in 1928, he was still Georgia Tom and still recording hokum songs.

We talked about hokum music right back in the earliest episodes of the podcast, but as a reminder, hokum music is a form which is now usually lumped into the blues by most of the few people who come across it, but which actually comes from vaudeville and especially from minstrel shows, and was hugely popular in the early decades of the twentieth century. It usually involved simple songs with a verse/chorus structure, and with lyrics that were an extended comedy metaphor, usually some form of innuendo about sex, with titles like “Meat Balls” and “Banana in Your Fruit Basket”.

As you can imagine, this kind of music is one that influenced a lot of people who went on to influence Little Richard, and it’s in this crossover genre which had elements of country, blues, and pop that we find “My Bucket’s Got a Hole in it” turning into the song that would later be known as “Keep A Knockin'”.

Tampa Red’s version was titled “You Can’t Come In”, and seems to have been the origin not only of “Keep A Knockin'” but also of the Lead Belly song “Midnight Special” — you can hear the similarity in the guitar melody:

[Excerpt: Tampa Red’s Hokum Jug Band, “You Can’t Come In”]

The version by Tampa Red’s Hokum Jug Band wasn’t the first recording to combine the “Keep a Knockin'” lyrics with the “My Bucket’s Got a Hole In It” melody — the piano player Bert Mays recorded a version a month earlier, and Mays and his producer Mayo Williams, one of the first black record producers, are usually credited as the songwriters as a result (with Little Richard also being credited on his version). Mays was in turn probably inspired by an earlier recording by James “Boodle It” Wiggins, but Wiggins had a different melody — Mays seems to be the one who first combined the lyrics with the “My Bucket’s Got a Hole In It” melody on a recording.

But the idea was probably one that had been knocking around for a while in various forms, given the number of different variations of the melody that turn up, and Tampa Red’s version inspired all the future recordings.

As hokum music lies at the roots of both blues and country, it’s not surprising that “You Can’t Come in” was picked up by both country and blues musicians. A version of the song, for example, was recorded by, among others, Milton Brown — who had been an early musical partner of Bob Wills and one of the people who helped create Western Swing.

[Excerpt: Milton Brown and his Musical Brownies: “Keep A Knockin'”]

But the version that Little Richard recorded was most likely inspired by Louis Jordan’s version. Jordan was, of course, Richard’s single biggest musical inspiration, so we can reasonably assume that the record by Jordan was the one that pushed him to record the song.

[Excerpt: Louis Jordan, “Keep A Knockin'”]

The Jordan record was probably brought to mind in 1955 when Smiley Lewis had a hit with Dave Bartholomew’s take on the idea. “I Hear You Knockin'” only bears a slight melodic resemblance to “Keep A Knockin'”, but the lyrics are so obviously inspired by the earlier song that it would have brought it to mind for anyone who had heard any of the earlier versions:

[Excerpt: Smiley Lewis, “I Hear You Knockin'”]

That was also recorded by Fats Domino, one of Little Richard’s favourite musicians, so we can be sure that Richard had heard it.

So by the time Little Richard came to record “Keep A Knockin'” in very early 1957, he had a host of different versions he could draw on for inspiration. But what we ended up with is something that’s uniquely Little Richard — something that was altogether wilder:

[Excerpt: Little Richard and his band, “Keep A Knockin'”]

In some takes of the song, Richard also sang a verse about drinking gin, which was based on Louis Jordan’s version which had a similar verse:

[Excerpt: Little Richard, “Keep A Knockin'”, “drinking gin” verse from take three]

But in the end, what they ended up with was only about fifty-seven seconds worth of usable recording. Listening to the session recording, it seems that Grady Gaines kept trying different things with his saxophone solo, and not all of them quite worked as well as might be hoped — there are a few infelicities in most of his solos, though not anything that you wouldn’t expect from a good player trying new things.

To get it to a usable length, they copied and pasted the whole song from the start of Richard’s vocal through to the end of the saxophone solo, and almost doubled the length of the song — the third and fourth verses, and the second saxophone solo, are the same recording as the first and second verses and the first sax solo. If you want to try this yourself, it seems that the “whoo” after the first “keep a knockin’ but you can’t come in” after the second sax solo is the point where the copy/pasting ends.

But even though the recording ended up being a bit of a Frankenstein’s monster, it remains one of Little Richard’s greatest tracks. At the same session, he also recorded another of his very best records, “Ooh! My Soul!”:

[Excerpt: Little Richard, “Ooh! My Soul!”]

That session also produced a single for Richard’s chauffeur, with Richard on the piano, released under the name “Pretty Boy”:

[Excerpt: Pretty Boy, “Bip Bop Bip”]

“Pretty Boy” would later go on to be better known as Don Covay, and would have great success as a soul singer and songwriter. He’s now probably best known for writing “Chain of Fools” for Aretha Franklin.

That session was a productive one, but other than one final session in October 1957, in which he knocked out a couple of blues songs as album fillers, it would be Little Richard’s last rock and roll recording session for several years.

Richard had always been deeply conflicted about… well, about everything, really. He was attracted to men as well as women, he loved rock and roll and rhythm and blues music, loved eating chitlins and pork chops, drinking, and taking drugs, and was unsure about his own gender identity. He was also deeply, deeply, religious, and a believer in the Seventh Day Adventist church, which believed that same-sex attraction, trans identities, and secular music were the work of the Devil, and that one should keep a vegetarian and kosher diet, and avoid all drugs, even caffeine.

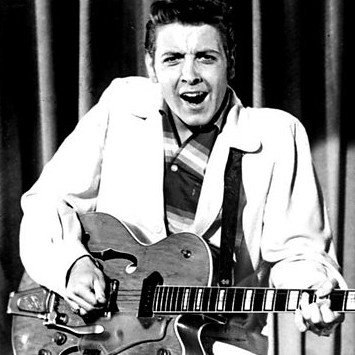

This came to a head in October 1957. Richard was on a tour of Australia with Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, and Alis Lesley, who was another of the many singers billed as “the female Elvis Presley”:

[Excerpt: Alis Lesley, “He Will Come Back To Me”]

Vincent actually had to miss the first couple of shows on the tour, as he and the Blue Caps got held up in Honolulu, apparently due to visa issues, and couldn’t continue on to Australia with the rest of the tour until that was sorted out. They were replaced on those early shows by a local group, Johnny O’Keefe and the Dee Jays, who performed some of Vincent’s songs as well as their own material, and who managed to win the audiences round even though they were irritated at Vincent’s absence.

O’Keefe isn’t someone we’re going to be able to discuss in much detail in this series, because he had very little impact outside of Australia. But within Australia, he’s something of a legend as their first home-grown rock and roll star. And he did make one record which people outside of Australia have heard of — his biggest hit, from 1958, “Wild One”, which has since been covered by, amongst others, Jerry Lee Lewis and Iggy Pop:

[Excerpt: Johnny O’Keefe, “Wild One”]

The flight to Australia was longer and more difficult than any Richard had experienced before, and at one point he looked out of the window and saw the engines glowing red. He became convinced that the plane was on fire, and being held up by angels. He became even more worried a couple of days later when Russia launched their first satellite, Sputnik, and it passed low over Australia — low enough that he claimed he could see it, like a fireball in the sky, while he was performing.

He decided this was a sign, and that he was being told by God that he needed to give up his life of sin and devote himself to religion. He told the other people on the tour this, but they didn’t believe him — until he threw all his rings into the ocean to prove it. He insisted on cancelling his appearances with ten days of the tour left to go and travelling back to the US with his band. He has often also claimed that the plane they were originally scheduled to fly back on crashed in the Pacific on the flight he would have been on — I’ve seen no evidence anywhere else of this, and I have looked.

When he got back, he cut one final session for Specialty, and then went into a seminary to start studying for the ministry.

While his religious belief is genuine, there has been some suggestion that this move wasn’t solely motivated by his conversion. Rather, John Marascalco has often claimed that Richard’s real reason for his conversion was based on more worldly considerations. Richard’s contract with Specialty was only paying him half a cent per record sold, which he considered far too low, and the wording of the contract only let him end it on either his own death or an act of god. He was trying — according to Marascalco — to claim that his religious awakening was an act of God, and so he should be allowed to break his contract and sign with another label.

Whatever the truth, Specialty had enough of a backlog of Little Richard recordings that they could keep issuing them for the next couple of years. Some of those, like “Good Golly Miss Molly” were as good as anything he had ever recorded. and rightly became big hits:

[Excerpt: Little Richard, “Good Golly Miss Molly”]

Many others, though, were substandard recordings that they originally had no plans to release — but with Richard effectively on strike and the demand for his recordings undiminished, they put out whatever they had.

Richard went out on the road as an evangelist, but also went to study to become a priest. He changed his whole lifestyle — he married a woman, although they would later divorce as, among other things, they weren’t sexually compatible. He stopped drinking and taking drugs, stopped even drinking coffee, and started eating only vegetables cooked in vegetable oil.

After the lawsuits over him quitting Specialty records were finally settled, he started recording again, but only gospel songs:

[Excerpt: Little Richard, “Precious Lord, Take My Hand”]

And that was how things stood for several years. The tension between Richard’s sexuality and his religion continued to torment him — he dropped out of the seminary after propositioning another male student, and he was arrested in a public toilet — but he continued his evangelism and gospel singing until October 1962, when he went on tour in the UK.

Just like the previous tour which had been a turning point in his life, this one featured Gene Vincent, but was also affected by Vincent’s work permit problems. This time, Vincent was allowed in the country but wasn’t allowed to perform on stage — so he appeared only as the compere, at least at the start of the tour — later on, he would sing “Be Bop A Lula” from offstage as well.

Vincent wasn’t the only one to have problems, either. Sam Cooke, who was the second-billed star for the show, was delayed and couldn’t make the first show, which was a bit of a disaster.

Richard was accompanied by a young gospel organ player named Billy Preston, and he’d agreed to the tour under the impression that he was going to be performing only his gospel music. Don Arden, the promoter, had been promoting it as Richard’s first rock and roll tour in five years, and the audience were very far from impressed when Richard came on stage in flowing white robes and started singing “Peace in the Valley” and other gospel songs.

Arden was apoplectic. If Richard didn’t start performing rock and roll songs soon, he would have to cancel the whole tour — an audience that wanted “Rip it Up” and “Long Tall Sally” and “Tutti Frutti” wasn’t going to put up with being preached at. Arden didn’t know what to do, and when Sam Cooke and his manager J.W. Alexander turned up to the second show, Arden had a talk with Alexander about it.

Alexander told Arden he had nothing to worry about — he knew Little Richard of old, and knew that Richard couldn’t stand to be upstaged. He also knew how good Sam Cooke was. Cooke was at the height of his success at this point, and he was an astonishing live performer, and so when he went out on stage and closed the first half, including an incendiary performance of “Twistin’ the Night Away” that left the audience applauding through the intermission, Richard knew he had to up his game.

While he’d not been performing rock and roll in public, he had been tempted back into the studio to record in his old style at least once before, when he’d joined his old group to record Fats Domino’s “I’m In Love Again”, for a single that didn’t get released until December 1962. The single was released as by “the World Famous Upsetters”, but the vocalist on the record was very recognisable:

[Excerpt: The World Famous Upsetters, “I’m In Love Again”]

So Richard’s willpower had been slowly bending, and Sam Cooke’s performance was the final straw. Little Richard was going to show everyone what star power really was.

When Richard came out on stage, he spent a whole minute in pitch darkness, with the band vamping, before a spotlight suddenly picked him out, in an all-white suit, and he launched into “Long Tall Sally”.

The British tour was a massive success, and Richard kept becoming wilder and more frantic on stage, as five years of pent up rock and roll burst out of him. Many shows he’d pull off most of his clothes and throw them into the audience, ending up dressed in just a bathrobe, on his knees. He would jump on the piano, and one night he even faked his own death, collapsing off the piano and lying still on the stage in the middle of a song, just to create a tension in the audience for when he suddenly jumped up and started singing “Tutti Frutti”.

The tour was successful enough, and Richard’s performances created such a buzz, that when the package tour itself finished Richard was booked for a few extra gigs, including one at the Tower Ballroom in New Brighton where he headlined a bill of local bands from around Merseyside, including one who had released their first single a few weeks earlier. He then went to Hamburg with that group, and spent two months hanging out with them and performing in the same kinds of clubs, and teaching their bass player how he made his “whoo” sounds when singing.

Richard was impressed enough by them that he got in touch with Art Rupe, who still had some contractual claim over Richard’s own recordings, to tell him about them, but Rupe said that he wasn’t interested in some English group, he just wanted Little Richard to go back into the studio and make more records for him.

Richard headed back to the US, leaving Billy Preston stranded in Hamburg with his new friends, the Beatles. At first, he still wouldn’t record any rock and roll music, other than one song that Sam Cooke wrote for him, “Well Alright”, but after another UK tour he started to see that people who had been inspired by him were having the kind of success he thought he was due himself. He went back into the studio, backed by a group including Don and Dewey, who had been performing with him in the UK, and recorded what was meant to be his comeback single, “Bama Lama Bama Loo”:

[Excerpt: Little Richard, “Bama Lama Bama Loo”]

Unfortunately, great as it was, that single didn’t do anything in the charts, and Richard spent the rest of the sixties making record after record that failed to chart. Some of them were as good as anything he’d done in his fifties heyday, but his five years away from rock and roll music had killed his career as a recording artist.

They hadn’t, though, killed him as a live performer, and he would spend the next fifty years touring, playing the hits he had recorded during that classic period from 1955 through 1957, with occasional breaks where he would be overcome by remorse, give up rock and roll music forever, and try to work as an evangelist and gospel singer, before the lure of material success and audience response brought him back to the world of sex and drugs and rock and roll.

He eventually gave up performing live a few years ago, as decades of outrageous stage performances had exacerbated his disabilities. His last public performance was in 2013, in Las Vegas, and he was in a wheelchair — but because he’s Little Richard, the wheelchair was made to look like a golden throne.

Next Episodes

Episode 53: "I Put a Spell on You" by Screamin' Jay Hawkins @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2019-10-21 06:58 / ⌛ 00:40:23

Episode 52: "Twenty Flight Rock", by Eddie Cochran @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2019-10-14 08:42 / ⌛ 00:35:39

Episode 52: “Twenty Flight Rock”, by Eddie Cochran @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2019-10-14 07:42

Episode 51: "Matchbox" by Carl Perkins @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2019-10-07 04:08 / ⌛ 00:35:03