"Mama He Treats Your Daughter Mean" by Ruth Brown

A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

Welcome to episode thirteen of A History of Rock Music in Five Hundred Songs. Today we're looking at "(Mama) He Treats Your Daughter Mean" by Ruth Brown. Click the full post to read liner notes, links to more information, and a transcript of the episode.

----more----

Resources

As always, I've created a Mixcloud streaming playlist with full versions of all the songs in the episode.

I used a few books for this podcast. One I haven't talked about before is Blue Rhythms: Six Lives in Rhythm and Blues by Chip Defaa.

The information on "Drinking Wine Spo-De-O-Dee" comes in part from Unsung Heroes of Rock 'n' Roll by Nick Tosches. This book is considered a classic, but a word of caution -- it was written in the 70s, and Tosches is clearly of the Lester Bangs/underground/gonzo school of rock journalism, which in modern terms means he's a bit of an edgelord who'll be needlessly offensive to get a laugh.

Much of the information I've used comes from interviews with Ruth Brown and Ahmet Ertegun in Honkers & Shouters: The Golden Years of Rhythm and Blues by Arnold Shaw, one of the most important books on early 50s rhythm and blues.

Ruth Brown also wrote an autobiography.

And there are many good compilations of Brown's R&B work -- this one has most of the important records on it.

Patreon

This podcast is brought to you by the generosity of my backers on Patreon. Why not join them?

Transcript

While I've often made the point that fifties rhythm and blues is not the same thing as "the blues" as most people now think of it, there was still an obvious connection (as you'd expect from the name if nothing else) and sometimes the two would be more connected than you might think. So Ruth Brown, who was almost the epitome of a rhythm and blues singer, had her first hit on the pop charts with a song that couldn't have been more blues inspired.

For the story of "Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean", we have to go all the way back to Blind Lemon Jefferson in the 1920s. Jefferson was a country-blues picker who was one of the most remarkable guitarists of his generation -- he was a blues man first and foremost, but his guitar playing influenced almost every country player who came later. Unfortunately, he recorded for Paramount Records, notoriously the label with the worst sound quality in the 20s and thirties (which, given the general sound quality of those early recordings, is saying something).

One of his songs was "One Dime Blues", which is a very typical example of his style:

[excerpt "One Dime Blues" by Blind Lemon Jefferson]

See what I mean both about the great guitar playing and about the really lousy sound quality?

That song was later picked up by another great blind bluesman, Blind Willie McTell.

McTell is an example of how white lovers of black music would manage to miss the point of the musicians they loved and try to turn them into something they're not. A substantial proportion of McTell's recordings were made by John and Alan Lomax, for the Library of Congress, but if you listen to those recordings you can hear the Lomaxes persuading McTell to play music that's very different from the songs he normally played -- while he was a commercial blues singer, they wanted him to perform traditional folk songs and to sing political protest material, and basically to be another Leadbelly (a singer he did resemble slightly as a musician, largely because they both played the twelve-string guitar). He said he didn't know any protest songs, but he did play various folk songs for them, even though they weren't in his normal repertoire.

And this is a very important thing to realise about the way the white collectors of black music distorted it -- and it's something you should also pay attention to when I talk about this stuff. I am, after all, a white man who loves a lot of black music but is disconnected from the culture that created it, just like the Lomaxes. There's a reason why I call this podcast "A History of Rock Music..." rather than "THE History of Rock Music..." -- the very last thing I want to do is give the impression that my opinion is the definitive one and that I should have the final word about these things.

But what the Lomaxes were doing, when they were collecting their recordings, was taking sophisticated entertainers, who made their living from playing to rather demanding crowds, and getting them to play music that the Lomaxes *thought* was typical black music, rather than the music that those musicians would normally play and that their audiences would normally listen to. So they got McTell to perform songs he knew, like "The Boll Weevil" and "Amazing Grace", because they thought that those songs were what they should be collecting, rather than having him perform his own material.

To put this into a context which may seem a little more obvious to my audience -- imagine you're a singer-songwriter in Britain in the present day. You've been playing the clubs for several years, you've got a repertoire of songs you've written which the audiences love. You get your big break with a record company, you go into the studio, and the producer insists on you singing "Itsy-Bitsy Spider" and a hymn you had to sing in school assembly like "All Things Bright and Beautiful". You probably could perform those, but you'd be wondering why they wouldn't let you sing your own songs, and what the audiences would think of you singing this kind of stuff, and who exactly was going to buy it.

But on the other hand, money is money, and you give the people paying you what they want.

This was the experience of a *lot* of black musicians in the thirties, forties, and fifties, having rich white men pay them to play music that they saw as unsophisticated. It's something we'll see particularly in the late fifties as musicians travel from the US to the UK, and people like Muddy Waters discovered that their English audiences didn't want to see anyone playing electric guitars and doing solos -- they thought of the blues as a kind of folk music, and so wanted to see a poor black sharecropper playing an acoustic guitar, and so that's what he gave those audiences.

But McTell's version of "One Dime Blues", retitled "Last Dime Blues", wasn't like that. That was the music he played normally, and it was a minor hit:

[excerpt: “Last Dime Blues” by Blind Willie McTell]

And that line we just heard, “Mama, don't treat your daughter mean”, inspired one of the most important records in early rock and roll.

Ruth Brown had run away from home when she was seventeen -- she'd wanted to become a singer, and she eloped with a trumpet player, Jimmy Brown, who she married and whose name she kept even though the marriage didn't last long.

She quickly joined Lucky Millinder's band, as so many early R&B stars we've discussed did, but that too didn't last long. Millinder's band, at the time, had two singers already, and the original plan was for Brown to travel with the band for a month and learn how they did things, and then to join them on stage. She did the travelling for a month part, but soon found herself kicked out when she got on stage.

She did two songs with the band on her first night performing live with them, and apparently went down well with the audience, but that was all she was meant to do on that show, so one of the other musicians asked her to go and get the band members drinks from the bar, as they were still performing. She brought them all sodas on to the stage... and Millinder said "I hired a singer, not a waitress -- you're fired. And besides, you don't sing well anyway".

She was fired that day, and she had no money -- Millinder refused to pay her, arguing that she'd had free room and board from him for a month, so if anything she owed him money. She had no way to make her way home from Washington. She was stuck.

But what should have been a terrible situation for her turned out to be the thing that changed her life. She got an audition with Blanche Calloway, Cab's sister, who was running a club at the time.

Well, I say Blanche Calloway was Cab's sister, and that's probably how most people today would think of her if they thought of her at all, but it would really be more appropriate to say Cab Calloway happened to be her brother.

Blanche Calloway had herself had a successful singing career, starting before her brother's career, and she'd recorded songs like this:

[excerpt "Just a Crazy Song": Blanche Calloway and her Joy Boys]

That was recorded several months *before* her brother's breakout hit "Minnie The Moocher", which popularised the "Hi de hi, ho de ho" chorus. Blanche Calloway wasn't the first person to sing that song – Bill “Bojangles” Robinson recorded it a month before, though in a very different style – but she's clearly the one who gave Cab the idea. She was a successful bandleader before her brother, and her band, the Joy Boys, featured musicians like Cozy Cole and Ben Webster, who later became some of the most famous names in jazz.

She was the first woman to lead an otherwise all-male band, and her band was regularly listed as one of the ten or so most influential bands of the early thirties. And that wasn't her only achievement by any means -- in later years she became prominent in the Democratic Party and as a civil rights activist, she started Afram, a cosmetic company that made makeup for black women and was one of the most popular brand names of the seventies, and she was the first black woman to vote in Florida, in 1958.

But while her band was popular in the thirties, it eventually broke up. There are two stories about how her band split, and possibly both are true. One story is that the Mafia, who controlled live music in the thirties, decided that there wasn't room for two bands led by a Calloway, and put their weight behind her brother, leaving her unable to get gigs. The other story is that while on tour in Mississippi, she used a public toilet that was designated whites-only, and while she was in jail for that one of the band members ran off with all the band's money and so she couldn't afford to pay them.

Either way, Calloway had gone into club management instead, and that was what she was doing when Ruth Brown walked into her club, desperate for a job.

Calloway said that the club didn't really need any new singers at the time, but she was sympathetic enough with Brown's plight -- and impressed enough by her talent -- that she agreed that Brown could continue to sing at her club until she'd earned her fare home.

And it was at that club that Willis Conover came to see her. Conover was a fascinating figure -- he presented the jazz programme on Voice of America, the radio station that broadcast propaganda to the Eastern bloc during the Cold War, but by doing so he managed to raise the profile of many of the greatest jazz musicians of the time. He was also a major figure in early science fiction fandom -- a book of his correspondence with H.P. Lovecraft is now available.

Conover was visiting the nightclub along with his friend Duke Ellington, and he was immediately impressed by Ruth Brown's performance -- impressed enough that he ran out to call Ahmet Ertegun and Herb Abramson and tell them to sign her.

Ertegun and Abramson were the founders of Atlantic Records, a new record label which had started up only a couple of years earlier.

We've talked a bit about how the white backroom people in early R&B were usually those who were in some ways on the borderline between American conceptions of race -- and this is something that will become even more important as the story goes on -- but that was certainly true of Ahmet Ertegun. Ertegun was considered white by the then-prevailing standards in the US, but he was a Turkish Muslim, and so not part of what the white culture considered the default.

He was also, though, extremely well off. His father had been the Turkish ambassador to the United States, and while young Ahmet had ostensibly been studying Medieval Philosophy at Georgetown University, in reality he was spending much of his time in Milt Gabler's Commodore Music Shop. He and his brother Neshui had over fifteen thousand jazz records between them, and would travel to places like New Orleans and Harlem to see musicians. And so Ahmet decided he was going to set up his own record company, making jazz records. He got funding from his dentist, and took on Herb Abramson, one of the dentist's proteges, as his partner in the firm. They soon switched from their initial plan of making jazz records to a new one of making blues and R&B, following the market.

Atlantic's first few records -- while they were good ones, featuring people like Professor Longhair, weren't especially successful, but then in 1949 they released "Drinking Wine Spo-De-O-Dee" by Sticks McGhee:

[excerpt "Drinking Wine Spo-De-O-Dee"]

That record is another of those which people refer to as "the first rock and roll record", and it was pure good luck for Atlantic -- McGhee had recorded an almost identical version two years earlier, for a label called Harlem Records. The song had originally been rather different -- before McGhee recorded it for Harlem Records, instead of singing spo-de-o-dee he'd sung a four-syllable word, the first two syllables of which were mother and the latter two would get this podcast put in the adults-only section on iTunes; while instead of singing "mop mop" he'd sung "goddam".

Wisely, Harlem Records had got him to tone down the lyrics, but the record had started to take off only after the original label had gone out of business. Ertegun knew McGhee's brother, the more famous blues musician Brownie McGhee, and called him up to get in touch with Sticks. They got Sticks to recut the record, sticking as closely as possible to his original, and rushed it out. The result was a massive success,and had cover versions by Lionel Hampton, Wynonie Harris, and many more musicians we've talked about here. Atlantic Records was on the map, and even though Sticks McGhee never had another hit, Atlantic now knew that the proto-rock-and-roll style of rhythm and blues was where its fortunes lay.

So when Herb Abramson and Ahmet Ertegun saw Ruth Brown, they knew two things -- firstly, this was a singer who had massive commercial potential, and secondly that if she was going to record for them, she'd have to change her style, from the torch songs she was singing to something more... spo-de-o-dee.

Ruth Brown very nearly never made it to her first recording session at all. On her way to New York, with Blanche Calloway, who had become her manager, she ended up in a car crash and was in hospital for a year, turning twenty-one in hospital. She thought for a time that her chance had passed, but when she got well enough to use crutches she was invited along to a recording session.

It wasn't meant to be a session for her, it was just a way to ease her back into her career -- Atlantic were going to show her what went on in a recording studio, so she would feel comfortable when it came to be time for her to actually make a record. The session was to record a few tracks for Cavalcade of Music, a radio show that profiled American composers. Eddie Condon's band were recording the tracks, and all Brown was meant to do was watch.

But then Ahmet Ertegun decided that while she was there, they might as well do a test recording of Brown, just to see whether her voice sounded decent when recorded. Herb Abramson -- who would produce most of Brown's early records -- listed a handful of songs that she might know that they could do, and she said she knew Russ Morgan's "So Long". The band worked out a rough head arrangement of it, and they started recording. After a few bars, though, Sid Catlett, the drummer -- one of the great jazz drummers, who had worked with Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman, among others -- stopped the session and said "Wait a minute. Let's go back and do this right. The kid can *sing*!"

And she certainly could. The record, which had originally been intended just as a test or, at best, as a track to stick in the package of tracks they were recording for Cavalcade of Music, was instead released as a single, by "Ruth Brown as heard with Eddie Condon's NBC Television Orchestra"

"So Long" became a hit, and the followup "Teardrops From My Eyes" was a bigger hit, reaching number one on the R&B charts and staying there for eleven weeks. "Teardrops From My Eyes" was an uptempo song, and not really the kind of thing Brown liked -- she thought of herself primarily as a torch singer -- but it can't be denied that she had a skill with that kind of material, even if it wasn't what she'd have been singing by choice:

[excerpt: Ruth Brown "Teardrops From My Eyes"]

While the song was picked for her by Abramson, who continued to be in charge of Brown's recordings until he was drafted into the Korean War, the strategy behind it was one that Ertegun had always advocated -- to take black musicians who played or sang the more "sophisticated" (I don't know if you can hear those air quotes, but they're there...) styles and to get them instead to record in funkier, more rhythm-oriented styles. It was a strategy Atlantic would use later with many of the artists that would become popular on the label in the 1950s.

In the case of "Teardrops From My Eyes", this required a lot of work -- Brown spent a week rehearsing the song with Louis Toombs, the song's writer, and working out the arrangement -- and this was in a time when most hit records were either head arrangements worked out in half an hour in the studio or songs that had been honed by months of live performance. Spending a week working out a song for a recording was extremely unusual, but it was part of Atlantic's ethos -- making sure the musicians were totally comfortable with the song and with each other before recording. It was the same reason that for the next few decades vocalists on Atlantic also played instruments on their own recordings, even if they weren't the best instrumentalists -- the idea was that the singer should be intimately involved in the rhythm of the record.

But it worked even better for Ruth Brown than for most of those artists. "Teardrops From My Eyes" became a million seller -- Atlantic's first. Or at least, it was promoted as having sold a million copies -- Herb Abramson would later claim that all the record labels were vastly exaggerating their sales. But then, he had a motive to claim that, just as they had a motive to exaggerate – if the artists believed they sold a million copies, then they'd want a million copies' worth of royalties.

But Brown's biggest hit was her third number one, "Mama He Treats Your Daughter Mean", which was also one of the few records she made to cross over to the pop charts, reaching number twenty-three. This was not a record that Brown thought at the time was particularly one of her best, but twenty years later in interviews she would talk about how she couldn't do a show without playing it and that when she said her name people would ask "the Ruth Brown who sings 'Mama He Treats Your Daughter Mean'?"

The song also made a difference to Brown because it meant she had to join the musicians' union. Vocalists, unlike instrumentalists, didn't have to be union members. But "Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean" had a prominent tambourine part, which Brown played live. That made her an instrumentalist, not just a vocalist, and so Brown became a union member.

[excerpt: "Mama He Treats Your Daughter Mean", Ruth Brown]

Johnny Wallace and Herbert Lance wrote that song after hearing a blues singer playing out on the street in Atlanta. The song the blues singer was playing was almost certainly “Last Dime Blues”, and contained a line which they heard as “Mama, he treats your daughter mean”.

Brown didn't want to record the song originally -- the way the song was originally presented to her was as a much slower blues -- but Herb Abramson raised the tempo to something closer to that of "Teardrops From My Eyes", turning it into a clear example of early rock and roll. You can hear the song's influence, for example, in "Work With Me Annie" by Hank Ballard and the Midnighters from two years later:

[Excerpt: "Work With Me Annie", Hank Ballard and the Midnighters]

But Brown always claimed that the reason for the song's greater success than her other records was down to that tambourine -- or more precisely because of the way she played the tambourine live, because she used a fluorescent painted tambourine which would shine when she hit it. That apparently got the audiences worked up and made it her most popular live song.

Brown continued to have hit records into the sixties, though she never became one of the most well-known artists -- in the seventies she used to talk about adults telling their children "she was our Aretha Franklin", and this was probably true. Certainly she was the most successful female rhythm and blues artist of the fifties, and was popular enough that for a while Atlantic Records became known as "the house that Ruth Brown built", but like many of the pioneers of the rock and roll era, she was largely (though far from completely) erased from the cultural memory in favour of a view that has prehistory start in 1954 with Elvis and history proper only arrive in 1962 with the Beatles.

Partly, this was because in the mid fifties, just as rock and roll was becoming huge, she had children and scaled down her touring activities to take care of them, but it was also in part because Atlantic Records was expanding. When they only had one or two big stars, it was easy for them to give each of them the attention they needed, but as the label got bigger, their star acts would have the best material divided among themselves, and their hit rate -- at least for those who didn't write their own material -- got lower.

So by the early sixties, Ruth Brown was something of a has-been. But she got a second wind from the late seventies onwards, after she appeared in the stage musical Selma, playing the part of Mahalia Jackson. She became a star again -- not a pop star as she had been in her first career, but a star of the musical stage, and of films and TV. And she used that fame to do something remarkable.

She had been unhappy for years with Atlantic Records not paying her the money she was owed for royalties on her records -- like most independent labels of the fifties, Atlantic had seemed to regard honouring its contracts with its artists and actually giving them money as a sort of optional extra. But unlike those other independent labels, Atlantic had remained successful, and indeed by the eighties it was a major label itself -- it had been bought in 1967 by Warner Brothers and had become one of the biggest record labels in the world. And Ruth Brown wanted the money to which she was entitled, and began a campaign to get the royalties she was owed.

But she didn't just campaign for herself. As part of the agreement she eventually reached with Atlantic, not only did she get her own money back, but dozens of other rhythm and blues artists also got their money -- and the Rhythm and Blues Foundation was founded with money donated by Atlantic as compensation for them. The Rhythm and Blues Foundation now provides grants to up-and-coming black musicians and gives cash awards to older musicians who've fallen on hard times -- often because of the way labels like Atlantic have treated them.

Now of course that's not to say that the Rhythm and Blues Foundation fixed everything -- it's very clear that Atlantic continued (and continues) to underpay the artists on whose work they built a billion-dollar business, and that the Foundation is one of those organisations that exists as much to forestall litigation as anything else, but it's still notable that when she had the opportunity to do something just for herself, Ruth Brown chose instead to also help her friends and colleagues. Maybe her time in the union paid off...

Brown spent her last decades as an elder stateswoman of the rhythm and blues field, She died in 2006.

Next Episodes

"Lawdy Miss Clawdy" by Lloyd Price @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2018-12-24 00:03 / ⌛ 00:31:07

“Lawdy Miss Clawdy” by Lloyd Price @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2018-12-24 00:03

Patreon Announcement @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2018-12-18 12:24 / ⌛ 00:00:23

Patreon Announcement @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2018-12-18 12:24

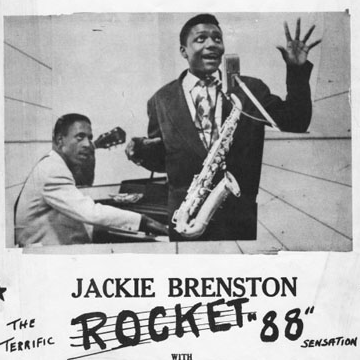

"Rocket 88" by Jackie Brenston and the Delta Cats @ A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

📆 2018-12-17 00:00 / ⌛ 00:28:56